Summary

Ankyloglossia is a congenital alteration of the base of the tongue responsible for some alterations in the development of speech, dentition and other aspects of adult life. For the implementation of the Ankyloglossia Outpatient Intervention Unit (UDIADEAN) in Primary Care, the prevalence of this pathology in the paediatric age of 0 to 14 years was determined. Method: During the first month of work, one of the authors of the study assessed the presence of ankyloglossia in all patients in their quota, attending the Health Center using the Hazelbaker morphological method in children under 6 months and Carmen Fernando in the elderly. Results: During the 17 working days of the month, a total of 443 patients of all age groups were attended. The reasons for consultation in 57 cases were due to a scheduled consultation at the “Control del Nen Sa”, in 76 controls were followed to previous visits with pathology and the rest were medical visits for frequent medical problems: cough, mucus, diarrhoea, vomiting and fever, among others. Of all the patients attended, 295 patients belonged to the paediatricians’ quota and in them an ankyloglossia prevalence of 31% was found.

Ankyloglossia, Tongue tie, Prevalence, Primary Health Care, Screening test, Diagnosis, Breastfeeding.

Complet text

Introduction

Ankyloglossia is a genetic malformation1 of the floor of the mouth that causes sucking difficulties in infants2 and causes various disorders in childhood, adolescence and adults: dyslalia, snoring, sleep apnea, atypical swallowing, skeletal disorders, dental disorders, among others3 .

It has been known since antiquity, although the health interest has been lost with the rise of bottle feeding. At the beginning of the 20th century, this malformation was habitually treated by midwives4in newborns. With the increase in breastfeeding has resurfaced this situation in infants, thus producing a significant increase in the demand for health interventions and, as a consequence, an increase in medical publications developing arguments for and against this intervention5 .

The prevalence of tongue tie has not been studied as such and the existing discrepancies in some studies in nearby areas show the lack of unanimity in the definition of ankyloglossia as well as for the diagnostic criteria of this malformation.

After one of the authors of the study joined a Primary Care Center as a pediatrician, during the first month of work, the presence of ankyloglossia or disorders related to this difficulty was assessed in all children aged 0 to 14 who attended the the consultation and that they belonged to the quota of patients assigned to him.

The objective of studying the prevalence of ankyloglossia in the area was to calculate an estimate of the situation prior to the creation in the Primary Care Center of an Intervention Unit in Primary Care of Ankyloglossia. (UDIDEAN).

Methods

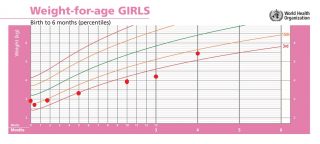

The existence of ankyloglossia was assessed in all attendees for any reason during the month of November 2015. Hazelbaker’s morphological criteria6 were followed in children under 6 months of age and in older adults the existence of ankyloglossia was assessed when tongue mobility was impaired. and following the criteria of Carmen Fernando 7.

The medical records of the patients visited with a diagnosis of Ankyloglossia were subsequently obtained and reviewed, and the following variables were recorded: reason for visit, diagnoses other than ankyloglossia, and presence of pathologies related to them and the presence of ankyloglossia.

The exit diagnoses of the children were studied at the end of the visit.

Results:

17 days were worked in the assignment CAP. In another four, the pediatrician was assigned to another health center and the data was not recorded because it was a population with another quota.

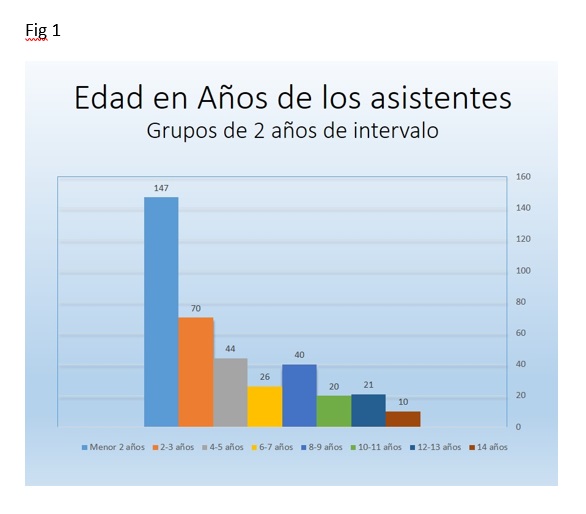

The total number of registered children was 443, of which 295 belonged to the main researcher’s quota, 106 were from the same Health Center, but from other quotas. 38 did not show up and 11 were from other clinics. The age range of the children visited with the highest attendance is from 0 to 4 years, in which there are 211, 71.5% of all those visited. Figure 1 shows the distribution by age groups.

Data was collected from 386 of those visited.

The reason for the visit for which the majority of patients with previously scheduled consultations attended was for control and follow-up of pathologies already diagnosed (76 cases), followed by well-child care visits (57 cases) and in 4 cases they were eating problems. The rest registered on the day as medical visits for pathologies of various types with greater or lesser urgency in the presentation: cough, runny nose, diarrhea, vomiting and fever, among others.

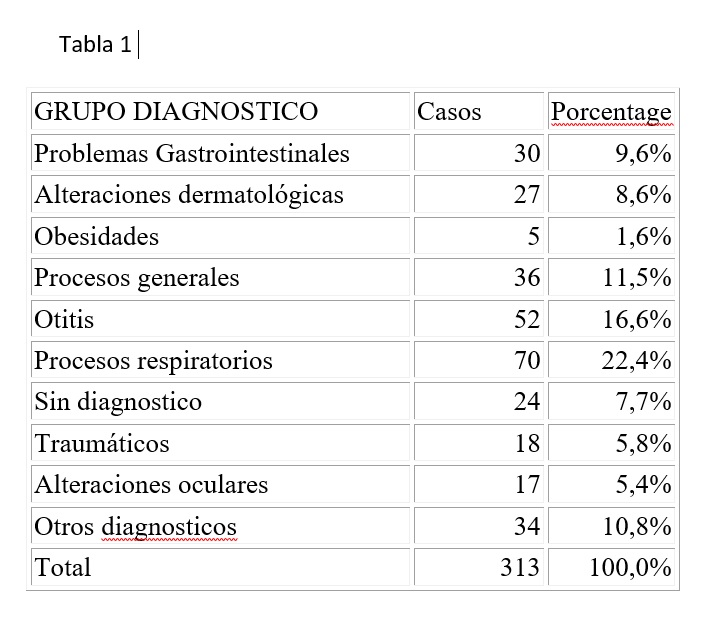

The diagnoses obtained at the end of the visit, in addition to ankyloglossia, were as shown in Table 1.

In fig. 2 you can see the number of visits per day, the ankyloglossia found and the daily percentage of this pathology.

According to these data, the prevalence of ankyloglossia in patients attending this health center with an age range between 0 and 14 years is 31.8% (95% CI: 29.8 – 33.76).

Discussion:

In Newborns we do not know the real incidence of this situation. In a study carried out in Israel, they found an incidence of lingual frenulum in 99% of children, although not all had ankyloglossia 8. In Brazil, since the mandatory implementation of the Martinelli Tongue test in all newborns, the incidence found in this age group is around 20% (Personal communication).

The data we have from our population does not show selection bias, since the pediatrician’s Curriculum was not known in the population of the area prior to their incorporation and the intention to create an Ankyloglossia Primary Care Intervention Unit (UDIADEAN) as stated in your contract. The individuals who attended the consultation did so for the usual causes in a health center unrelated to the ankyloglossia. The age distribution data is similar to other primary care centers 10. The ages studied are similar to the population pyramid of the Municipality.

The results of the prevalence of ankyloglossia in our population are higher than those usually found in the literature. In most studies, the figure is 5%, based on and referencing the Messner 11 study carried out in the year 2000, which diagnosed ankyloglossia subjectively.

Other subsequent studies that give prevalence figures were not planned with this objective.

In the study carried out in Asturias where they tried to evaluate the prevalence, the data from the Province studied gave an average of 12%, with areas with a prevalence of 50% and others less than 5%12 . Prevalence data in older children show a prevalence similar to ours when the prevalence of this situation is specifically studied 13.

Our study is in the total child population attending the CAP. The power of the study does not allow comparison with other studies of specific incidences for different ages, although the observed trend is that it confirms those that show a higher prevalence than currently considered.

At UDIADEAN we are studying the prevalence, assessing all newborns with the Martinelli’s tongue test 9 and the Hazelbaker Morphology test 6, which make it possible to identify ankyloglossia that generates sucking disorders and determines the intervention of this pathological fixation at an early age.

The lack of a unified and consensual diagnostic method is one of the reasons for the variability in the prevalence of this alteration appreciated in the diagnostic opinions of health workers in the different studies carried out.

When one of the four most well-known diagnostic methods is systematically used, the health comment ceases to be a medical opinion 14, it is a diagnosis and we could compare it scientifically.

The opinion that some health professionals make about the non-existence of ankyloglossia in the consultation, sometimes without palpating the frenulum to assess elasticity or without determining the exit of the tongue outside the lip simply by looking at the baby’s mouth is not enough to determine the existence of this alteration and obviously the felt incidence will be much less than the real one.

In the work of the UDIADEAN Group carried out since 2016, in the frenectomies performed both in the health center and those carried out in the reference hospital with the previous assessment of the Hazelbaker test and giving this positive, we have noticed an improvement in the sucking of babies and decrease in discomfort reported by the mother as seen in other previous studies 15.

We believe that using some form of diagnosis is a condition prior to concretely determining the incidence and prevalence of this disorder 16. Unifying the diagnostic criteria for Ankyloglossia will allow us to carry out comparative studies on the prevalence of this pathology in the general population in different areas, which we believe is underdiagnosed.

REFERENCES

[1] Ruiz Guzmán L, Cueva Quiroz T, Rodríguez Bailón N, Rubira Felices L, Peña C, Gabarrell Guiu C. Herencia de la anquiloglosia: de tal palo, tal astilla. Rev Pediatr Aten Primaria. 2019;21.

[2] Campanha SMA, Martinelli RLC, Palhares, DB. Association between ankyloglossia and breastfeeding. CoDAS, 31(1), e20170264. Epub February 25, 2019.https://doi.org/10.1590/2317-1782/20182018264

[3] Hong P, Lago D, Seargeant J, Pellman L, Magit AE, Pransky SM. Defining ankyloglossia: a case series of anterior and posterior tongue ties. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74:1003-6.

[4] Cullun IM. An old wives’ tale. Br Med J. 1959;2:497-8.

[5] Bin-Nun A, Kasirer YM, Mimouni FB A Dramatic Increase in Tongue Tie-Related Articles: A 67 Years Systematic Review. Breastfeed Med. 2017 Sep;12(7):410-414. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2017.0044.

[6] Hazelbaker AK. The assessment tool for lingual frenulum function (ATLFF). Use in a lactation consultant private practice [Thesis]. Los Angeles: Pacific Oaks College; 1993.

[7] Fernando C. Tongue tie: From confussion to clarity. A guide to the diagnosis and treatment of Ankiloglossia (tongue tie). Sidney: Tandem publications; 1998.

[8] Haham A, Marom R, Mangel L, Botzer E, Dollberg S. Prevalence of breastfeeding difficulties in newborns with a lingual frenulum: a prospective cohort series. Breastfeed Med. 2014 Nov;9(9):438-41. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2014.0040. Epub 2014 Sep 19.

[9] Martinelli RLC, Marchesan IQ, Berretin-Felix G. Protocolo de avaliação do frênulo lingual para bebês: relação entre aspectos anatômicos e funcionais. Rev Cefac. 2013;15:599-610 [en línea] [consultado el 04/05/2019]. Disponible en http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rcefac/v15n3/162-11.pdf

[10] L. A. García Llop, A. Asensi Alcoverro. C. Grafiá Juan, P. Coll Mas. Estudio de la demanda en Atención Primaria pediátrica. An Esp Pediatr 1996;44:469-474. https://www.aeped.es/sites/default/files/anales/44-5-15.pdf

[11] Messner AH1, Lalakea ML, Aby J, Macmahon J, Bair E. Ankyloglossia: incidence and associated feeding difficulties. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000 Jan;126(1):36-9.

[12]González Jiménez D, Costa Romero M, Riaño Galán I, González Martínez MT, Rodríguez Pando MC, Lobete Prieto C. Prevalencia de anquiloglosia en recién nacidos en el Principado de Asturias. An Pediatr (Barc). 2014 Aug;81(2):115-9.

[13] Gutiérrez Centeno LY. Prevalencia de anquiloglosia en escolares de 6 a 12 años del nivel primario de las escuelas públicas de los municipios de Zacualpa y San Miguel. Tesis de Grado de Cirugía Dental. Universidad de San Carlos. Guatemala 2006. http://biblioteca.usac.edu.gt/tesis/09/09_1833.pdf

[14] Diez V, Ruiz MM, Peña C, Calderón J, González C, Ruiz L. Estudio comparativo de métodos de diagnóstico de anquiloglosia en el lactante. Poster presentado en el XIV Congreso Fedalma. Villafranca del Penedes 2017. http://www.elfrenillolingual.com

[15]Francis DO, Krishnaswami S, McPheeters M. Treatment of Ankyloglossia and Breastfeeding Outcomes: A Systematic Review. PEDIATRICS Volume 135, number 6, 1-10. 2015. www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2015-0658

[16]Hill R1.Implications of Ankyloglossia on Breastfeeding. Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2019 Mar/Apr;44(2):73-79. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000501